Pharma risks could rise under deregulation

Reprints

President Donald Trump has vowed to reduce U.S. pharmaceutical prices, but a potential de-emphasis on testing the effectiveness of drugs at the regulatory level could affect the risk profile of companies in the sector.

“The U.S. drug companies have produced extraordinary results for our country, but the pricing has been astronomical for our country,” the president said after meeting with pharmaceutical industry leaders at the White House in January. “We have to lower the drug prices.”

Insurers are concerned that some actions the administration could take to reduce pricing might heighten risk and litigation potential for pharmaceutical firms, said Walker Taylor, Wilmington, North Carolina-based managing director of Arthur J. Gallagher & Co.’s life sciences practice.

“I appreciate his willingness to try to put more supply of product out there or get these drugs approved faster or loosen some regulations,” he said. But “I’ve talked to some underwriters at insurance companies, and I know they are concerned about anything that weakens pre-emption defenses, reduces oversight of post-marketing surveillance or could be perceived or argued by plaintiffs class action counsel as decreasing the certainty of safety for profits.”

“I get what Trump is saying as far as ‘Hey, the prices are too high,’ but on the other hand, that’s the cost of having these miraculous new drugs and having an incredibly safe marketplace,” Mr. Taylor added.

The president has pledged to expedite pharmaceutical reviews done by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Specific details have not been released, but there are growing concerns that this effort could diminish the focus on testing drugs’ efficacy.

While Phase 1 drug trials emphasize safety, the emphasis in Phase 2 is on effectiveness — whether the drug works for those with a particular disease or condition.

“The length of time it takes to get a drug approved is largely related to the efficacy standard,” said Jur Strobos, partner in the health care and intellectual property practices of law firm Baker McKenzie in Washington. “The efficacy standard is statutory. I don’t think that people in the scientific, medical or even the pharmaceutical industry actually have that much of an interest in lowering the efficacy bar.”

The president’s rumored nominees to lead the FDA are driving part of this concern, including libertarian Jim O’Neill, who has argued that drugmakers should not have to prove the efficacy of drugs in clinical trials. The idea of not testing for efficacy is an extreme proposal that has raised numerous concerns, said Dr. Bill Bithoney, chief physician executive at The BDO Center for Healthcare Excellence & Innovation based in New York.

“Do we want drugs that have not been tested for efficacy?” he said. “There’s a strong contingent of people who believe the current efficacy tests are inadequate ... If there is a true libertarian movement away from efficacy testing and only having safety testing, that may well lower the cost of medication, but could put the public more at risk.”

A speedier FDA review process that lowers or eliminates emphasis on efficacy could lead to additional litigation against pharmaceutical companies, experts say.

“Getting a drug approved by the FDA does not immunize somebody from a lawsuit,” said Simon Elliott, senior counsel with law firm Foley & Lardner L.L.P. in Washington. “If something was brought into the market without FDA proving that it was effective, you can just imagine someone saying, ‘I was made sick and this drug wasn’t fully approved by the FDA.’ I’m not saying it’s a fair argument, but it would have more weight.”

Underwriters would be concerned about lessening the focus on efficacy because “ultimately if it’s not effective, safety concerns will pop up,” Mr. Taylor said.

John Connolly, North American practice leader for life science and pharmaceuticals with Willis Towers Watson P.L.C. based in Radnor, Pennsylvania, said a de-emphasis on efficacy at the regulatory level could impose a greater burden on drugmakers to monitor it post-approval.

“You will be expected to monitor your patient population of any new product much more closely than you have in the past, and if you see a variance in adverse effects, failure of the drug to work, patient deaths, there will be a higher-than-ever duty to swiftly report back to the FDA and update any warnings on your labels,” he said. “That would lead to an increased risk.”

Read Next

-

Pharma product liability capacity plentiful, D&O exposures grow

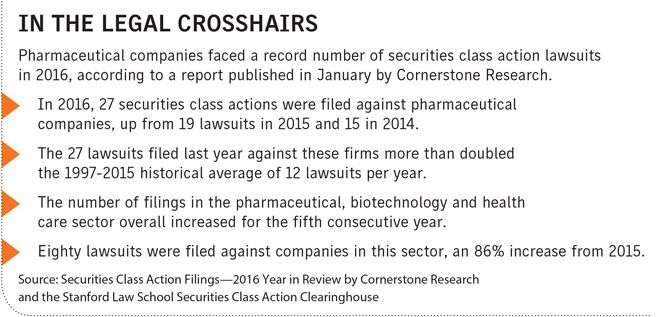

Pharmaceutical companies are increasingly the target of securities litigation, making it a difficult risk to insure, but the market is generally still very favorable for buyers seeking product liability coverage.